AN APPENDIX

The censures which, I am informed, have been made on the foregoing essay inclined me to think I had not been clear and express enough in some points, and to prevent being misunderstood for the future, I was willing to make any necessary alterations or additions in what I had written. But that was impracticable, the present edition having been almost finished before I received this information. Wherefore I think it proper to consider in this place the principal objections that are come to my notice.

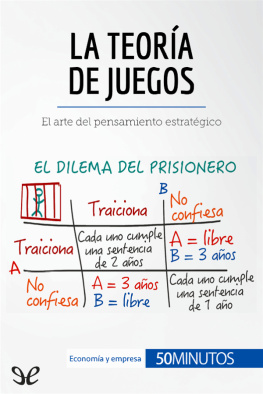

In the first place it’s objected that in the beginning of the essay I argue either against all use of lines and angles in optics, and then what I say is false; or against those writers only who will have it that we can perceive by sense the optic axes, angles, etc., and then it’s insignificant, this being an absurdity which no one ever held. To which I answer that I argue only against those who are of opinion that we perceive the distance of objects by lines and angles or, as they term it, by a kind of innate geometry. And to shew that this is not fighting with my own shadow, I shall here set down a passage from the celebrated Descartes.

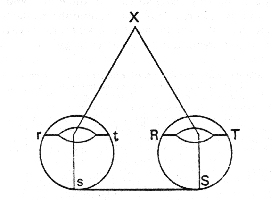

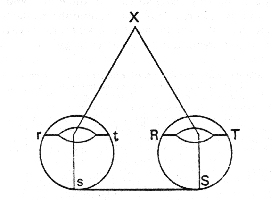

Distantiam praeterea discimus, per mutuam quandam conspirationem oculorum. Ut enim caecus noster duo bacilla tenens AE et CE, de quorum longitudine incertus, solumque intervallum manuum A et C, cum magnitudine angulorum ACE, et CAE exploratum habens, inde, ut ex geometria quadam omnibus innata, scire potest ubi sit punctum E. Sic quum nostri oculi RST et rst ambo, vertuntur ad X, magnitudo lineae Ss, et angulorum XSs et XsS, certos nos reddunt ubi sit punctum X. Et idem opera alterutrius possumus indagare, loco illum movendo, ut si versus X illum semper dirigentes, primo sistamus in puncto S, et statim post in puncto s, hoc sufficiet ut magnitudo lineae Ss, et duorum anguloruin XSs et XsS nostrae imaginationi simul occurrant, et distantiam puncti X nos edoceant; idquc per actionem mentis, quae licet simplex judicium esse videatur, ratiocinationem tamen quandam involutam habet, similem illi, qua geometrae per duas stationes diversas, loca inaccessa dimetiuntur.

I might amass together citations from several authors to the same purpose, but this being so clear in the point, and from an author of so great note, X shall not trouble the reader with any more. What I have said on this head was not for the sake of finding fault with other men, but because I judged it necessary to demonstrate in the first place that we neither see distance immediately, nor yet perceive it by the mediation of anything that hath (as lines and angles) a necessary connexion with it. For on the demonstration of this point the whole theory depends.

Secondly, it is objected that the explication I give of the appearance of the horizontal moon (which may also be applyed to the sun) is the same that Gassendus had given before. I answer, there is indeed mention made of the grossness of the atmosphere in both, but then the methods wherein it is applyed to solve the phaenomenon are widely different, as will be evident to whoever shall compare what X have said on this subject with the following words of Gassendus.

Heinc dici posse videtur: solem humilem oculo spectatum ideo apparerc majorem, quam dum altius egreditur, quia dum vicinus est horizonti prolixa est series vaporum, atque adeo corpusculorum quae solis radios ita retundunt, ut oculus minus conniveat, et pupilla quasi umbrefacta longe magis amplificetur, quam dum sole multum elato rari vapores intercipiuntur, solque ipse ita splendescit, ut pupilla in ipsum spectans contractissima efiiciatur. Nempe ex hoc esse videtur, cur visibilis specics ex sole procedens, et per pupillam amplificatam intromissa in retinara, ampliorem in illa sedem occupet, majorcmque proinde creet solis apparentiam, quam dum per contractam pupillam eodem intromissa contendit (vid. Epist. I de apparente Magnitudine solis humilis et sublimis, page 6).

This solution of Gassendus proceeds on a false principie, viz., That the pupils being enlarged, augments the species or image on the fund of the eye.

Thirdly, against what is said in sect. LXXX, it is objected that the same thing which is so small as scarce to be discerned by a man may appear like a mountain to some small insect; from which it follows that the minimum visibile is not equal in respect of all creatures. I answer, if this objection be sounded to the bottom it will be found to mean no more than that the same particle of matter, which is marked to a man by one minimum visibile, exhibits to an insect a great number of minima visibilia. But this does not prove that one minimum visibile of the insect is not equal to one mínimum visibile of the man. The not distinguishing between the mediate and immediate objects of sight is, I suspect, a cause of misapprehension in this matter.

Some other misinterpretations and difficulties have been made, but in the points they refer to I have endeavoured to be so very plain that I know not how to express myself more clearly. All I shall add is that if they who are pleased to criticise on my essay would but read the whole over with some attention, they might be the better able to comprehend my meaning and consequently to judge of my mistakes.

I am informed that, soon after the first edition of this treatise a man somewhere near London was made to see, who had been born blind, and continued so for about twenty years. Such a one may be supposed a proper judge to decide how far some tenents laid down in several places of the foregoing essay are agreeable to truth, and if any curious person hath the opportunity of making proper interrogatories to him thereon, I should gladly see my notions either amended or confirmed by experience.

GEORGE BERKELEY (Dysert, Irlanda, 12 de marzo de 1685 - Cloyne, Irlanda, 14 de enero de 1753). Filósofo irlandés y uno de los representantes del empirismo inglés.

Entres sus obras se encuentran: Arithmetica (1707), Miscellanea Mathematica (1707), Philosophical Commentaries or Common-Place Book (1707–08, notebooks), An Essay towards a New Theory of Vision (1709), A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, Part I (1710), Passive Obedience, or the Christian doctrine of not resisting the Supreme Power (1712), Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous (1713), An Essay Towards Preventing the Ruin of Great Britain (1721), De Motu (1721), A Proposal for Better Supplying Churches in our Foreign Plantations, and for converting the Savage Americans to Christianity by a College to be erected in the Summer Islands (1725), A Sermon preached before the incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (1732), Alciphron, or the Minute Philosopher (1732), The Theory of Vision, or Visual Language, shewing the immediate presence and providence of a Deity, vindicated and explained (1733), The Analyst: a Discourse addressed to an Infidel Mathematician (1734), A Defence of Free-thinking in Mathematics, with Appendix concerning Mr. Walton’s vindication of Sir Isaac Newton’ Principle of Fluxions (1735), Reasons for not replying to Mr. Walton’s Full Answer (1735), The Querist, containing several queries proposed to the consideration of the public (three parts, 1735-7), A Discourse addressed to Magistrates and Men of Authority (1736), Siris, a chain of philosophical reflections and inquiries, concerning the virtues of tar-water (1744), A Letter to the Roman Catholics of the Diocese of Cloyne (1745), A Word to the Wise, or an exhortation to the Roman Catholic clergy of Ireland (1749), Maxims concerning Patriotism (1750), Farther Thoughts on Tar-water (1752), Miscellany (1752).